-

Home

-

About

-

Research Intro

-

Childrens Lit

-

Curriculum

The editors intended for this volume to provide queer and ally athletes a space to have a voice and share the experiences that have been significant in their identity as an athletic member of the LGBT+ community. To that end, this book is a collection of autobiographical short stories of LGBT+ athletes and their experiences in sports and athletics, some who are publicly out and some who are not. Based on the narratives collected, the book is organized around themes that illustrate various perspectives and the power that sport can play in (1) finding one’s true identity, (2) bridging communities, and (3) challenging gender norm stereotypes.

The goal of this book is to help change the expectations of what it means to be a successful athlete and promote greater inclusivity of LGBT athletes. Providing the space for these voices to be heard will help to pave the way for a non-discriminating sporting environment, allow LGBT+ athletes to focus on their given sport without any distractions, and enable these athletes to live an authentic life without having to hide their true identity.

Jeff contributed to the following piece in Queer Voices from the Locker Room:

A Sissy Speaks To Gym Teachers: How I Was Formed And Deformed By Toxic Masculinity

By

Jeff Sapp

That Was Then

I don’t recall what happened in third-grade, but I was suddenly different. In first and second-grades Philip, Danny, Rick and I had been best friends. But not in third-grade. In third-grade I remember them isolating me. What had happened? Why was it different now? Was it because they all wore their baseball caps to school that fall from their summer little league teams?

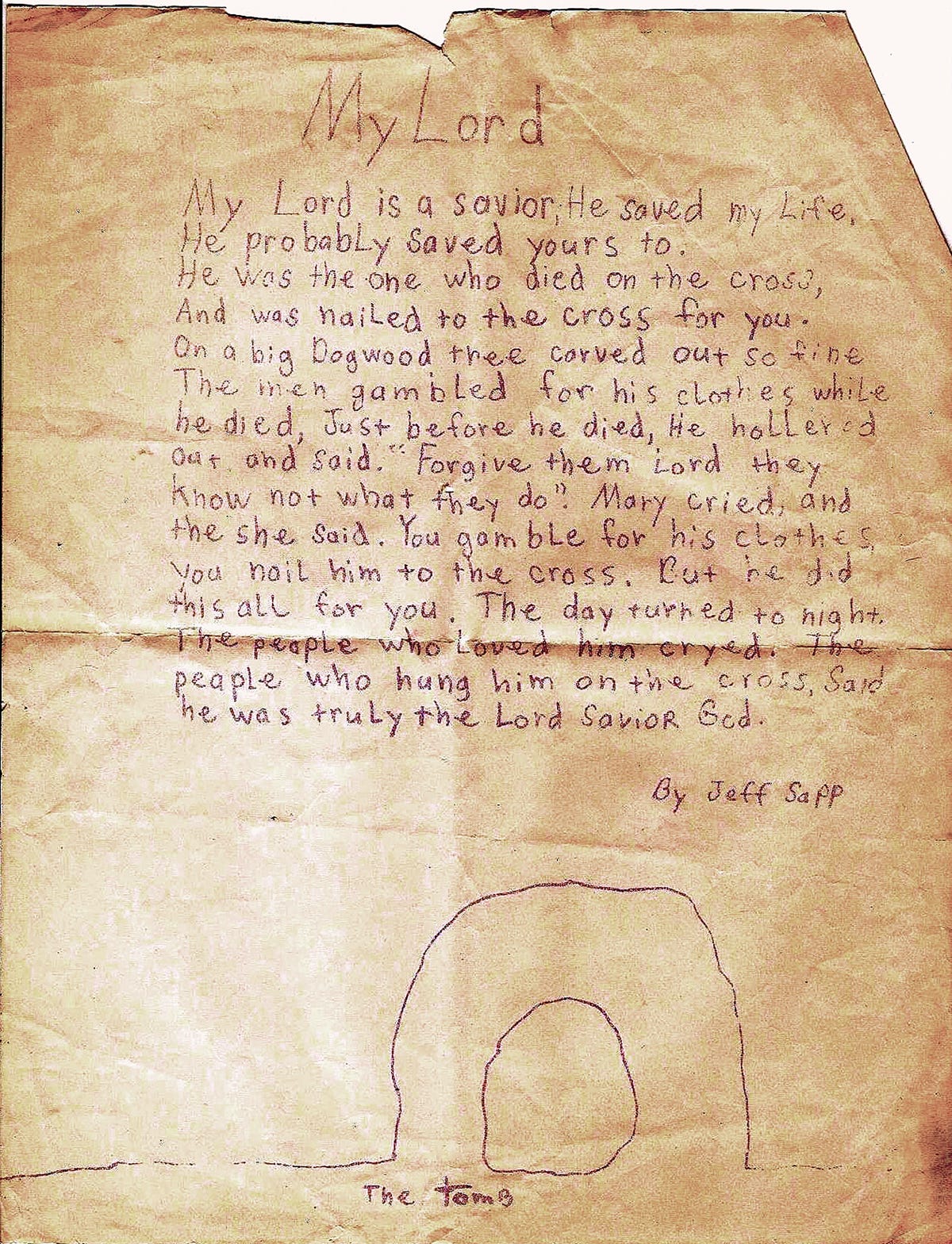

In fifth-grade I wrote a poem about Easter and Mrs. Porter printed it and gave it out to the entire class (see Appendix A). She raved and raved about how good it was and what a wonderful writer I was. I was so proud of that little poem that even today, decades later, I still have the purple ditto Easter poem tucked away in an old cigar box in a closet full of childhood memories. But I was clueless at 10-years of age that being known for poetry instead of little league would be a bad thing. I also remember recess the day my poem hit the 5th-grade press. “Smear the Queer” was the playground focus and, since I was so obviously an Oscar Wilde, the boys came at me like the Green Bay Packers. This memory, too, is tucked away in an old memory box in a closet full of childhood remembrances.

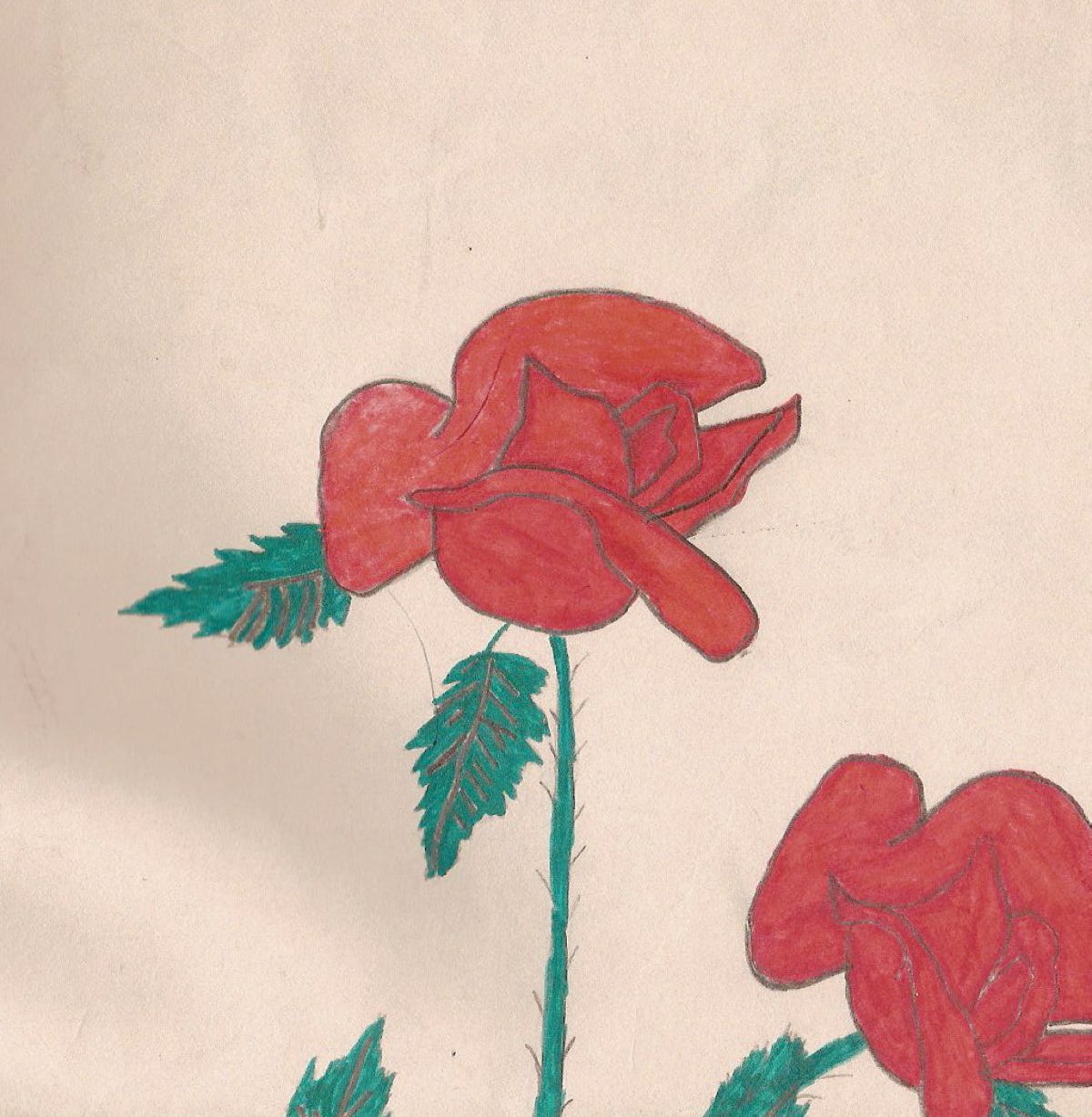

I remember drawing a wild rose for the school art contest (see Appendix B). It was connected to our science lessons on Appalachian wildflowers and I was proud that I had made an academic connection in my art project. I won a blue ribbon. Yes, it was for participation, but it was still an honor, as I had never won anything before this. I still have that piece of art framed and hanging on my bedroom wall today as a way to honor my elementary years even though I am many years away from them today. I think it is good to have a part of sixth-grade with you always. It reminds you of things. My sixth-grade teacher, Miss Gibbs, also had us learn about the medicinal properties of wildflowers as well as their edible parts. We had to demonstrate our culinary knowledge to the class and I remember making jam out of the petals of the same wild roses I had drawn for my art project. Can you imagine how my popularity grew? First a poet, next an artist, and finally a chef! To the other boys, it was like I had leprosy. I remember being called so many names by my boy peers during my school years. First a queer, next a homo, and finally a fag. School is an absolute torture for those of us boys who do not fit into the narrow constructs of gender and masculinity that have been spoon fed to us since we were born.

Remember the gym rope in sixth-grade? I can feel the eyes of all the other sixth-grade boys watching me try to pull the full weight of my own 86 pounds up to the ceiling. It’s true that most are not paying attention. Several particularly insightful and self-confident peers are cheering me on. “Come on Jeff! I know you can do it! Just a little more! You’re half way there!” A couple are giggling. Knowing I’ll give up like I did last gym period. And the one before that. The gym teacher is among those that smirk. How have my ears been so trained to hear those soft, un-encouraging giggles and not hear those loud cries of support?

I have such a great memory for detail that it actually shocks me that I can’t remember this next teacher’s name. I know it started with a “W” but that is all my memory can squeeze out. Mr. W was my seventh-grade shop teacher. He was also the middle school football coach and he had coached each one of my three older brothers, introducing them to the manly sport of football. And, today, so many years after he pinned me to the shop class wall and threatened and terrorized me, I find myself writing about him because my experience with him seems unresolved.

I was scared to death of shop class in the first place. Being raised by a single mother in the 50s, I hadn’t had the luxury of a father who would have given me the prerequisites I needed for shop class. The only tools I’d known were the garden tools I’d used to weed the pansies in my flower garden. Anyway, what remains unresolved for me is why he targeted me and, seemingly, not other classmates. He came at me nice enough the first week of school.

“I’ve had all the Sapp boys in football,” he said. “I take it you’ll be joining the team too?”

I have no idea how I said “No” but I did and he was enraged. He actually pinned me against the wall and said in a low, quiet mafia voice, “You will join the team.” After that, he asked me every class period, growing more and more angry each time. And, finally, once the actual football season started he stopped speaking to me and only threw wrenches at me. It was his classroom management style to throw wrenches at those students who weren’t paying attention to him. To my knowledge he never actually hit anyone with a wrench. No, his tactic was simply to terrorize you with fear in hopes, I guess, that you’d saw your finger off or something like that.

Today my adult-self holds the quivering, sweaty hand of that little boy and asks: “Why is he picking on us?”

There are only two rational answers my adult-self can come up with. One, my brothers or my Mom had spoken with Mr. W and told him that I grew pansies in my flower garden and that I needed to be hit regularly by ninth-graders to rid myself of my flower-fetish. Or, two, Mr. W was not really a teacher at all, but a terrorist. But, surely they don’t allow terrorists to teach children in school…or do they?

When is it that you realize that you are a sissy? What age? What grade? Who lets you know that you aren’t like the other boys?

High school gym class petrified me. I’m serious. I mean absolutely petrified me. I’d have rather faced the living dead and fought zombies then dress out for gym class and, once again, be reminded of how I wasn’t like the other boys. I remember that I eventually just started hiding in the library, among books that for some reason comforted me. And I carefully forged absent slips from my mom that addressed my horrible illness, an illness so terrible that I should not be allowed to exercise. And even though I used different colored ink to forge my mom’s name for the different days I had missed, I wasn’t quite as clever as I’d thought and I was busted for skipping class. The gym teacher was so disgusted at me, the same gym teacher that used gender as motivation. “Okay girls,” he’d say to the all male class, “Surely you can do more pushups than that?”

It’s no wonder I had such a difficult academic time in my public school years as a child. Truth is, I had entirely too much curriculum to negotiate. Learning to read and write, classifying plants and animals, doing reports on state history, negotiating gender norming roles, deciphering why I was attracted to boys, passing as a heterosexual, and trying to fend off the bullies who saw my difference as weakness. It felt as if I was swimming up stream while everyone else seemed to be going with the current. I was simply too exhausted by the time I got to sentence diagramming and long division to concentrate on it. My grades suffered. And my sense of self suffered even more. It still affects me today. I have a daughter now and when we are at a play date and the other fathers are in the living room watching and bonding over a soccer game, I do not join them. I hate sports, for the most part. I do not for a second want to use sports as a way to bond. And, so, I remain on the outside of the father club, still a spectator. It still feels exactly like that summer going into third-grade when the other boys - strutting the school in their baseball caps - wouldn’t speak to me.

Toxic Masculinity

Perhaps nowhere on a school campus is the construction of masculinities more apparent than in the physical education class and its extracurricular counterpart of school athletics. Pascoe (2012) notes that schools are a major socializing institution in the life of children and, sadly, it is a dominant place where boys learn heteronormative and homophobic discourses, practices, and interactions and internalize them into adulthood. Boys often lay claim to their own masculine identities by hurling homophobic epithets at other boys and engaging in misogynistic discussions of girls’ bodies too. I am not the first to write about the toxic terrain of physical education in the school setting (Davison, 2004; Kehler & Atkinson, 2010) and I won’t be the last. As a matter of fact, all one needs to do to learn about the devastating and lasting impact of toxic masculinity as a result of physical education classes is to ask about men’s memories of it in any personal circle. Toxic masculinity - the socially constructed attitudes that describe expressions of maleness as violent, unemotional, aggressive, domineering, and controlling – is harmful to everyone.

The Gym Teacher I Wish I Had

As a former child terrorized by gym class and now as a veteran teacher educator, what is it that I wish I’d had in a physical educator? What kind of space would I have flourished in as a timid sissy-child? What could have occurred that would have had me fall in love with health and fitness as a way of life? Here are overarching pedagogies I urge physical educators to be aware of and implement. You don’t have to be a physical educator to implement these strategies. We all have children in our lives and these three ways of being with children can work anywhere, not just in a gym class. Stop telling young boys children that they are “studs” and young girl children that they are such a “pretty princess” and begin complimenting boys on their kind spirit and girls on their fierce strength. Anyone can use the following three ways of being with children. Anyone. Anywhere. Any time.

Be explicitly safe. First and foremost, there must be a cornerstone of building relationships and trust within the class (Fitzpatrick, 2010). I encourage physical education professionals to begin their school year by discussing issues of gender, masculinities and homophobia. Tell students what is appropriate and what is inappropriate and take a stand for social and mental wellbeing as well as the physical wellbeing of your students. Lay out exactly what kind of a climate you want in your class and remain diligently consistent in modeling and guiding students towards it. Do not privileged athletes who, because of their athletic performances often reside in schools with positions of power and prestige in schools. Instead, enlist them as team leaders and train them about your classroom climate, having them to model true leadership as those who make physical fitness spaces safe for all students. Give athletes responsibilities to be exemplary leaders within the school community who aid you in making your gym class the most popular and safe space on campus. Not a gym teacher? Okay, then have as many conversations as you can about gender with children. Challenge gender norms, policing, and stereotyping.

Be explicitly pro-feminist. Understand there are societal and institutional forces against you being a loving, caring male. All too often sexism and homophobia walk comfortably hand-in-hand (Pharr, 1997). When you are anti-woman in any form it communicates to boys in your class that sexism is okay. When you are homophobic it typically is in a form that disparages the feminine (“You throw like a girl!”) and this communicates that anything associated with the feminine is negative and less-than. Being pro-feminist is effort well spent for all males (hooks, 2004). Gorski (2008) states five reasons it is important for men to be pro-feminist. First, violence against women in all of its forms – sexual harassment, rape, domestic violence – is a form of terrorism. Secondly, hyper-masculinity contributes to other forms of violence in the world. Thirdly, patriarchal gender roles limit everyone’s ability to live and contribute fully to society. Fourth of all, male privilege perpetuates a system of oppression. Gorski’s fifth reason is a powerful one as well. His fifth reason is his Grandmother. Think of the womyn in your own life as well. And then reflect on whether your day-to-day interactions are anti-sexist and anti-oppressive. Go further and become a student of all things gender related in school cultures (Butler-Wall et al., 2016) and model excellence to the boys you’re bringing into manhood.

Be explicitly non-toxic in your masculinity. Of course, this means that each individual educator must work through their own internalized issues around gender constructs so that they can comfortably teach these topics in a genuine and authentic manner. Just this very week I had students in my teaching credential course speak about their most memorable teachers. Two physical educators spoke of the same gym teacher they had in high school and how he really was tough on them and made them “man up. “ Honestly, the teacher they were speaking of sounded like a horrible bully to me. My two students shared their pride in surviving his masculinity hazing and how it made them the men there were today. I could only think of how they were going to treat students in the same brutalizing manner to make “boys into men.” I am struck by a Quaker tenet I heard once at a school I’d written about (Sapp, 2005) when I wrote an article on holistic education – teaching to body, mind, and spirit. The tenet was, “Strong women, gentle men.” I see strong womyn all around me but, honestly, I rarely ever see gentle men. Fight against toxic masculinity in all its forms. Be better than the shallow Hollywood portrayals of men that are consumed daily in the media. Be gentle. To this day, I am always stunned by heterosexual men who are comfortable in their own sexuality and are not threatened by a queer man in their presence; it is more unusual than you would think to have men of strength reach out and be kind and loving to queer men in their midst. I recently reunited with a former student of mine from twenty years ago named Matt. Matt was amazing even as a young college man and I remember him once grabbing my hand and walking across a school campus holding it. When I saw him recently it was with his wife and two children and he still held my hand, kissed my cheek, and wept with emotion at seeing his mentor. He brought me a gift. He had his high school students - students in another state who have never met me - write me notes of appreciation for being the teacher who had impacted and shaped him the most. It was so touching. Matt reminds me that there are gentle men out in the world who have rejected toxic masculinity and are safe and kind. Be like Matt.

Be explicitly on the lookout for gender non-conforming students in your classroom. I suspect if you do the three above pedagogical practices that they’ll be less need for you to actually look and monitor those students that were like myself, kids that didn’t fit the gender norms. Still, though, look for us. And look out for us. I do not mean to “look out after us” in a patriarchal manner where you are an overseer, but in a way that demonstrates your ethic of caring. Seek us out and be our leaders as well, even though we’re not your best students and don’t exhibit physical prowess. We will try harder if you know our names and we feel like we have our own personal connections with you as a teacher and a leader. Your kindness can inspire us to involve ourselves in fitness for life, and isn’t that your goal? Again, if you’re not in a classroom, just notice the children around you with eyes that see them for their character and not for the way they perform gender.

This Is Now

I find an odd joy in being a teacher educator that has future physical education teachers in my teacher credential courses today. There they sit. Terrorists. And I stand before them now as a veteran of many years in teaching and speak to them of becoming a teacher. Of becoming a caring teacher. Of becoming an aware teacher. Of becoming.

The first thing I tell them is that I wish I’d learned “fitness as a way of life” in gym class. Instead, I learned that I was a worthless sissy that was always to be picked last for any team. I struggled with health and well being in my adulthood as a result of this. I became an athlete later in life…a runner, a swimmer, and an accomplished 20-year career veteran lifeguard and lifeguard instructor. But I grieve not running track in high school; it’s one of the few regrets I have in life. How will those adults who model fitness and health embrace and encourage the sissy who would rather be in the library than in the gym class? Will the rewards only be for those gifted athletes who come equipped with the physical skills for success? How will teams be picked? Who will be the captains? Will you stand guard against the homophobia or will you let The Lord of the Flies attitudes take over? Will gender violence be given a shoulder shrug and a boys-will-be-boys wink?

I remember a time when I hated waking up for school. I hated hearing the alarm go off. I hated seeing the light invade in around the perimeter of the blinds. I hated leaving the familiar blankets wrapped around me like a cocoon. I hated that I would have to spend another entire day trying to figure out what teachers and peers were telling me about gender and why I felt so incredibly alone in a school full of thousands of children the same age as I was. I hated that I was the sissy boy that was always picked last for gym class. To this day, I hate waking up in the morning, but I am suddenly struck by how much I missed because I slept far too long.

Bibliography

Butler-Wall, A., Cosier, K., Harper, R. L. S., Sapp, J., Sokolower, J. & Bollow Tempel, M. (2016). Rethinking

sexism, gender, and sexuality. Milwaukee, WI: Rethinking Schools.

Davison, K. G. (2004). Texting gender and body as a distant/ced memory: An autobiographical account of

bodies, masculinities and schooling. The Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 20(3):129-149.

Gorski, P. (2008). The evolution of a pro-feminist. Retrieved from http://www.edchange.org/publications/

pro-feminist.pdf

Fitzpatrick, K. (2010). A critical multicultural approach to physical education: Challenging discourses of

physicality and building resistant practices in schools. In Stephen May and Christine E. Sleeters (eds.)

Critical multicultural theory and praxis. New York, NY: Routledge.

hooks, b. (2004). The will to change: Men, masculinity, and love. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Kehler, M. & Atkinson, M. (2010). Boys’ bodies: Speaking the unspoken. New York, NY: Peter Lang

Publishing.

Pascoe, C. J. (2012). Dude, you’re a fag: Masculinity and sexuality in high school. Berkeley, CA: University of

California Press.

Pharr, S. (1997). Homophobia: A weapon of sexism. Berkeley, CA: Chardon Press.

Sapp, J. (2005). Body, mind & spirit: Holistic educators seek authentic connections with students, subjects,

colleagues and the world. Teaching Tolerance Magazine, 27.

Appendix A

Appendix B

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Aliquam tincidunt lorem enim, eget fringilla turpis congue vitae. Phasellus